In much of Western Europe, he is remembered as the epitome of cruelty and rapacity. However, in Hungary, Turkey, and other Turkic-speaking countries in Central Asia, he is regarded as a hero and his name is revered.[citation needed]

Background

The Huns were a group of Eurasian nomads, appearing from beyond the Volga, who migrated into Europe c. 370 and built up an enormous empire there. Their main military techniques were mounted archery and javelin throwing. They were possibly the descendants of the Xiongnu who had been northern neighbours of China three hundred years before and may be the first expansion of Turkic people across Eurasia. The origin and language of the Huns has been the subject of debate for centuries. One scholar suggests a relationship to Yeniseian. According to some theories, their leaders at least may have spoken a Turkic language, perhaps closest to the modern Chuvash language.

The death of Rugila (also known as Rua or Ruga) in 434 left the sons of his brother Mundzuk (Hungarian: Bendegúz, Turkish: Boncuk), Attila and Bleda (Buda), in control of the united Hun tribes. At the time of two brothers' accession, the Hun tribes were bargaining with Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II's envoys for the return of several renegades (possibly Hunnic nobles who disagreed with the brothers' assumption of leadership) who had taken refuge within the Eastern Roman Empire.

The following year Attila and Bleda met with the imperial legation at Margus (present-day Požarevac) and, all seated on horseback in the Hunnic manner, negotiated a successful treaty. The Romans agreed to not only return the fugitives, but to also double their previous tribute of 350 Roman pounds (ca. 115 kg) of gold, to open their markets to Hunnish traders, and to pay a ransom of eight solidi for each Roman taken prisoner by the Huns. The Huns, satisfied with the treaty, decamped from the Roman Empire and returned to their home in the Hungarian Great Plain, perhaps to consolidate and strengthen their empire. Theodosius used this opportunity to strengthen the walls of Constantinople, building the city's first sea wall, and to build up his border defenses along the Danube.

The Huns remained out of Roman sight for the next few years while they invaded the Sassanid Empire. When defeated in Armenia by the Sassanids, the Huns abandoned their invasion and turned their attentions back to Europe. In 440 they reappeared in force on the borders of the Roman Empire, attacking the merchants at the market on the north bank of the Danube that had been established by the treaty. Crossing the Danube, they laid waste to the cities of Illyricum and forts on the river, including (according to Priscus) Viminacium, a city of Moesia. Their advance began at Margus, where they demanded that the Romans turn over a bishop who had retained property that Attila regarded as his. While the Romans discussed turning the Bishop over, he slipped away secretly to the Huns and betrayed the city to them.

While the Huns attacked city-states along the Danube, the Vandals led by Geiseric captured the Western Roman province of Africa and its capital of Carthage. Carthage was the richest province of the Western empire and a main source of food for Rome. The Sassanid Shah Yazdegerd II invaded Armenia in 441. The Romans stripped the Balkan area of forces needed to defeat the Vandals in Africa which left Attila and Bleda a clear path through Illyricum into the Balkans, which they invaded in 441. The Hunnish army sacked Margus and Viminacium, and then took Singidunum (modern Belgrade) and Sirmium. During 442 Theodosius recalled his troops from Sicily and ordered a large issue of new coins to finance operations against the Huns. Believing he could defeat the Huns, he refused the Hunnish kings' demands.

Attila responded with a campaign in 443. Striking along the Danube, the Huns, equipped with new military weapons like the battering rams and rolling siege towers, overran the military centres of Ratiara and successfully besieged Naissus (modern Niš).

Advancing along the Nisava River, the Huns next took Serdica, Philippopolis, and Arcadiopolis. They encountered and destroyed a Roman army outside Constantinople but were stopped by the double walls of the Eastern capital. They defeated a second army near Callipolis (modern Gallipoli). Theodosius, stripped of his armed forces, admitted defeat, sending the Magister militum per Orientem Anatolius to negotiate peace terms. The terms were harsher than the previous treaty: the Emperor agreed to hand over 6,000 Roman pounds (ca. 2000 kg) of gold as punishment for having disobeyed the terms of the treaty during the invasion; the yearly tribute was tripled, rising to 2,100 Roman pounds (ca. 700 kg) in gold; and the ransom for each Roman prisoner rose to 12 solidi.

Their demands met for a time, the Hun kings withdrew into the interior of their empire. According to Jordanes (following Priscus), following the Huns' withdrawal from Byzantium (probably around 445), Bleda died, killed in a hunting accident arranged by his brother, Attila. Attila then took the throne for himself, becoming the sole ruler of the Huns.

Sole ruler

In 447 Attila again rode south into the Eastern Roman Empire through Moesia. The Roman army under the Gothic magister militum Arnegisclus met him in the Battle of the Utus and was defeated, though not without inflicting heavy losses. The Huns were left unopposed and rampaged through the Balkans as far as Thermopylae. Constantinople itself was saved by the Isaurian troops of the magister militum per Orientem Zeno and protected by the intervention of the prefect Constantinus, who organized the reconstruction of the walls that had been previously damaged by earthquakes, and, in some places, to construct a new line of fortification in front of the old. An account of this invasion survives:

The barbarian nation of the Huns, which was in Thrace, became so great that more than a hundred cities were captured and Constantinople almost came into danger and most men fled from it. ... And there were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great numbers. (Callinicus, in his Life of Saint Hypatius)

In the West

In 450, Attila proclaimed his intent to attack the powerful Visigoth kingdom of Toulouse, making an alliance with Emperor Valentinian III in order to do so. He had previously been on good terms with the Western Roman Empire and its influential general Flavius Aëtius. Aëtius had spent a brief exile among the Huns in 433, and the troops Attila provided against the Goths and Bagaudae had helped earn him the largely honorary title of magister militum in the west. The gifts and diplomatic efforts of Geiseric, who opposed and feared the Visigoths, may also have influenced Attila's plans.

However, Valentinian's sister was Honoria, who, in order to escape her forced betrothal to a Roman senator, had sent the Hunnish king a plea for help – and her engagement ring – in the spring of 450. Though Honoria may not have intended a proposal of marriage, Attila chose to interpret her message as such. He accepted, asking for half of the western Empire as dowry. When Valentinian discovered the plan, only the influence of his mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile, rather than kill, Honoria. He also wrote to Attila strenuously denying the legitimacy of the supposed marriage proposal. Attila sent an emissary to Ravenna to proclaim that Honoria was innocent, that the proposal had been legitimate, and that he would come to claim what was rightfully his.

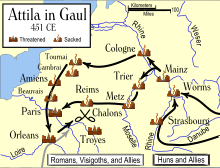

Attila interfered in a succession struggle after the death of a Frankish ruler. Attila supported the elder son, while Aëtius supported the younger. Attila gathered his vassals—Gepids, Ostrogoths, Rugians, Scirians, Heruls, Thuringians, Alans, Burgundians, among others and began his march west. In 451, he arrived in Belgica with an army exaggerated by Jordanes to half a million strong. J.B. Bury believes that Attila's intent, by the time he marched west, was to extend his kingdom – already the strongest on the continent – across Gaul to the Atlantic Ocean.

On April 7, he captured Metz. Other cities attacked can be determined by the hagiographic vitae written to commemorate their bishops: Nicasius was slaughtered before the altar of his church in Rheims; Servatus is alleged to have saved Tongeren with his prayers, as Saint Genevieve is to have saved Paris. Lupus, bishop of Troyes, is also credited with saving his city by meeting Attila in person.

Aëtius moved to oppose Attila, gathering troops from among the Franks, the Burgundians, and the Celts. A mission by Avitus, and Attila's continued westward advance, convinced the Visigoth king Theodoric I (Theodorid) to ally with the Romans. The combined armies reached Orléans ahead of Attila, thus checking and turning back the Hunnish advance. Aëtius gave chase and caught the Huns at a place usually assumed to be near Catalaunum (modern Châlons-en-Champagne). The two armies clashed in the Battle of Châlons, whose outcome is commonly considered to be a strategic victory for the Visigothic-Roman alliance. Theodoric was killed in the fighting and Aëtius failed to press his advantage, according to Edward Gibbon and Edward Creasy, because he feared the consequences of an overwhelming Visigothic triumph as much as he did a defeat. From Aëtius' point of view, the best outcome was what occurred: Theodoric died, Attila was in retreat and disarray, and the Romans had the benefit of appearing victorious.

Invasion of Italy and death

Attila returned in 452 to claim his marriage to Honoria anew, invading and ravaging Italy along the way. The city of Venice was founded as a result of these attacks when the residents fled to small islands in the Venetian Lagoon. His army sacked numerous cities and razed Aquileia completely, leaving no trace of it behind. Legend has it he built a castle on top of a hill north of Aquileia to watch the city burn, thus founding the town of Udine, where the castle can still be found. Aëtius, who lacked the strength to offer battle, managed to harass and slow Attila's advance with only a shadow force. Attila finally halted at the River Po. By this point disease and starvation may have broken out in Attila's camp, thus helping to stop his invasion.

Emperor Valentinian III sent three envoys, the high civilian officers Gennadius Avienus and Trigetius, as well as the Bishop of Rome Leo I, who met Attila at Mincio in the vicinity of Mantua, and obtained from him the promise that he would withdraw from Italy and negotiate peace with the emperor. Prosper of Aquitaine gives a short, reliable description of the historic meeting, but gives all the credit of the successful negotiation to Leo. Priscus reports that superstitious fear of the fate of Alaric—who died shortly after sacking Rome in 410—gave him pause.

In reality, Italy had suffered from a terrible famine in 451 and her crops were faring little better in 452; Attila's devastating invasion of the plains of northern Italy this year did not improve the harvest. To advance on Rome would have required supplies which were not available in Italy, and taking the city would not have improved Attila's supply situation. Therefore, it was more profitable for Attila to conclude peace and retreat back to his homeland. Secondly, an East Roman force had crossed the Danube under the command of another officer also named Aetius—who had participated in the Council of Chalcedon the previous year—and proceeded to defeat the Huns who had been left behind by Attila to safeguard their home territories. Attila, hence, faced heavy human and natural pressures to retire "from Italy without ever setting foot south of the Po." As Hydatius writes:

The Huns, who had been plundering Italy and who had also stormed a number of cities, were victims of divine punishment, being visited with heaven-sent disasters: famine and some kind of disaster. In addition, they were slaughtered by auxiliaries sent by the Emperor Marcian and led by Aetius, at the same time, they were crushed in their [home] settlements....Thus crushed, they made peace with the Romans and all retired to their homes.—Hydatius, Chron Min. ii pp.26ff

After Attila left Italy and returned to his palace across the Danube, he planned to strike at Constantinople again and reclaim the tribute which Marcian had stopped. (Marcian was the successor of Theodosius and had ceased paying tribute in late 450 while Attila was occupied in the west; multiple invasions by the Huns and others had left the Balkans with little to plunder.) However Attila died in the early months of 453. The conventional account, from Priscus, says that at a feast celebrating his latest marriage to the beautiful and young Ildico (if uncorrupted, the name suggests a Gothic origin) he suffered a severe nosebleed and choked to death in a stupor. An alternative theory is that he succumbed to internal bleeding after heavy drinking or a condition called esophageal varices, where dilated veins in the lower part of the esophagus rupture leading to death by hemorrhage.

Another account of his death, first recorded 80 years after the events by the Roman chronicler Count Marcellinus, reports that "Attila, King of the Huns and ravager of the provinces of Europe, was pierced by the hand and blade of his wife." The Volsunga saga and the Poetic Edda also claim that King Atli (Attila) died at the hands of his wife, Gudrun. Most scholars reject these accounts as no more than hearsay, preferring instead the account given by Attila's contemporary Priscus. Priscus' version, however, has recently come under renewed scrutiny by Michael A. Babcock. Based on detailed philological analysis, Babcock concludes that the account of natural death, given by Priscus, was an ecclesiastical "cover story" and that Emperor Marcian (who ruled the Eastern Roman Empire from 450 to 457) was the political force behind Attila's death.

Jordanes says: "The greatest of all warriors should be mourned with no feminine lamentations and with no tears, but with the blood of men." His horsemen galloped in circles around the silken tent where Attila lay in state, singing in his dirge, according to Cassiodorus and Jordanes: "Who can rate this as death, when none believes it calls for vengeance?"

Then they celebrated a strava (lamentation) over his burial place with great feasting. Legend says that he was laid to rest in a triple coffin made of gold, silver, and iron, along with some of the spoils of his conquests. His men diverted a section of the river, buried the coffin under the riverbed, and then were killed to keep the exact location a secret.

His sons Ellac (his appointed successor), Dengizich, and Ernakh fought over the division of his legacy, specifically which vassal kings would belong to which brother. As a consequence they were divided, defeated and scattered the following year in the Battle of Nedao by the Ostrogoths and the Gepids under Ardaric who had been Attila's most prized chieftain.

Attila's many children and relatives are known by name and some even by deeds, but soon valid genealogical sources all but dry up and there seems to be no verifiable way to trace Attila's descendants. This has not stopped many genealogists from attempting to reconstruct a valid line of descent for various medieval rulers. One of the most credible claims has been that of the khans of Bulgaria (see Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans). A popular, but ultimately unconfirmed, attempt tries to relate Attila to Charlemagne.

Etymology of the name

The origin of Attila's name is not known with confidence. Pritsak considers it to mean "universal ruler" in a Turkic language related to Danube Bulgarian. Maenchen-Helfen suggests an East Germanic origin and rejects a Turkic etymology: "Attila is formed from Gothic or Gepidic atta, "father," by means of the diminutive suffix -ila." He suggests that Pritsak's etymology is "ingenious but for many reasons unacceptable". However, he suggests that these names were "not the true names of the Hun princes and lords. What we have are Hunnic names in Germanic dress, modified to fit the Gothic tongue, or popular Gothic etymologies, or both. Mikkola thought Attila might go back to Turkish atlïg, "famous"; [127] Poucha finds in it Tokharian atär, "hero." [128] The first etymology is too farfetched to be taken seriously, the second is nonsense."

The name has many variants in modern languages: Atli and Atle in Norse, Attila/Atilla/Etele in Hungarian (all the three name variants are used in Hungary; Attila is the most popular variant), Etzel in the German Nibelungenlied, or Attila, Atila or Atilla in modern Turkish.

Appearance, character

There is no surviving first-person account of Attila's appearance. There is, however, a possible second-hand source, provided by Jordanes, who cites a description given by Priscus. It suggests a person of Asian features.

Attila has been portrayed in various ways, sometimes as a noble ruler, sometimes as a cruel barbarian. Attila is known in Western history and tradition as the grim flagellum dei (Latin: "Scourge of God"), and his name has become a byword for cruelty and barbarism. Some of this may have arisen from confusion between him and later steppe warlords such as Genghis Khan and Timur (Tamerlane). All have been regarded as cruel, clever, and blood-thirsty lovers of battle and pillage; all have been recorded mainly by their enemies. The reality of his character is probably more complex. Priscus also recounts his meeting with an eastern Roman captive who admired Hunnic governance over Roman, so that he had no desire to return to his former country, and the Byzantine historian's description of Attila's humility and simplicity is unambiguous in its admiration.[citation needed]

Later folklore and iconography

Legendary accounts of the meeting of Leo I and Attila, a pious "fable which has been represented by the pencil of Raphael and the chisel of Algardi" (as Gibbon called it) say that the Pope, aided by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, convinced Attila to turn away from the city.[citation needed] According to a version of this legend related in the Chronicon Pictum, a mediaeval Hungarian chronicle, the Pope promised Attila that if he left Rome in peace, one of his successors would receive a holy crown (which has been understood as referring to the Holy Crown of Hungary).

Some histories and chronicles describe him as a great and noble king, and he plays major roles in three Norse sagas: Atlakviða, Völsungasaga, and Atlamál. The Polish Chronicle represents Attila's name as Aquila.[citation needed]

In modern Hungary and in Turkey "Attila" and its Turkish variation "Atilla" are commonly used as a male first name. In Hungary, several public places are named after Attila; for instance, in Budapest there are 10 Attila Streets, one of which is an important street behind the Buda Castle, and an Attila Lane. See Public place names of Budapest.[citation needed] When the Turkish Armed Forces invaded in Cyprus in 1974 the operations were named after Attila (Atilla I & Atilla II).

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attila