Al-Idrisi's education was probably acquired in Andalusia.

Early life

Al-Idrisi traced his descent through long line of Princes, Caliphs and Sufi leaders, to The Prophet Muhammad. His immediate forebears, the Hammudids (1016–1058), were an offshoot of the Idrisids (789-985) of Morocco. He was of both Berber and Arab descend.

Al-Idrisi's was born in Ceuta, where his great-grandfather had fled after the fall of Málaga in Al-Andalus (1057). He spent much of his early life travelling through North Africa, and Spain and seems to have acquired a detail information on both regions. He visited Anatolia when he was barely 16. He is known to have studied in Córdoba, and later taught in Constantine, Algeria.

Apparently his travels took him to many parts of Europe including Portugal, the Pyrenees, the French Atlantic coast and Jórvík also known as York, in England.

Tabula Rogeriana

Born and raised in Ceuta at an early age al-Idrisi travelled to Islamic Spain, Portugal, France and England, he visited Anatolia when he was barely 16, because of conflict and instability in Andalusia al-Idrisi joined his other contemporaries such as Abu al-Salt in Sicily, where the Normans had overthrown Arabs formerly loyal to the Fatimids, according to Ibn Jubayr: "the Normans tolerated and patronized a few Arab families in exchange for knowledge"

Al-Idrisi incorporated the knowledge of Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East gathered by Islamic merchants and explorers recorded on Islamic maps, and with the information brought by the Normans voyagers to create the most accurate map of the world in pre-modern times, which seved as a concrete illustration of his Kitab nuzhat al-mushtaq, (Latin: Opus Geographicum), which may be translated A Diversion for the Man Longing to Travel to Far-Off Places.

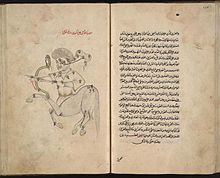

The Tabula Rogeriana was drawn by Al-Idrisi in 1154 for the Norman King Roger II of Sicily, after a stay of eighteen years at his court, where he worked on the commentaries and illustrations of the map. The map, with legends written in Arabic, while showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, only shows the northern part of the African continent and lacks details of the Horn of Africa and Southeast Asia.

For Roger it was inscribed on a massive disc of solid silver, two metres in diameter.

On the geographical work of al-Idrisi, S.P. Scott wrote in 1904:

The compilation of Edrisi marks an era in the history of science. Not only is its historical information most interesting and valuable, but its descriptions of many parts of the earth are still authoritative. For three centuries geographers copied his maps without alteration. The relative position of the lakes which form the Nile, as delineated in his work, does not differ greatly from that established by Baker and Stanley more than seven hundred years afterwards, and their number is the same. The mechanical genius of the author was not inferior to his erudition. The celestial and terrestrial planisphere of silver which he constructed for his royal patron was nearly six feet in diameter, and weighed four hundred and fifty pounds; upon the one side the zodiac and the constellations, upon the other-divided for convenience into segments-the bodies of land and water, with the respective situations of the various countries, were engraved.[2]

Al-Idrisi inspired Islamic geographers such as Ibn Battuta, Ibn Khaldun, Piri Reis and the Barbary Corsairs. His map also inspired Christopher Columbus and Vasco Da Gama.

Nuzhatul Mushtaq

As well as the maps, al-Idrisi produced a compendium of geographical information with the title Kitab nuzhat al-mushtaq fi'khtiraq al-'afaq. The title has been translated as The book of pleasant journeys into faraway lands or The pleasure of him who longs to cross the horizons.

Publication and translation

An abridged version of the Arabic text was published in Rome in 1592 with title: De geographia universali or Kitāb Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī dhikr al-amṣār wa-al-aqṭār wa-al-buldān wa-al-juzur wa-al-madā’ in wa-al-āfāq which in English would be Recreation of the desirer in the account of cities, regions, countries, islands, towns, and distant lands.This was one of the first Arabic books ever printed.The first translation from the original Arabic was into Latin. The Maronites Gabriel Sionita and Joannes Hesronita translated an abridged version of the text which was published in Paris in 1619 with the rather misleading title of Geographia nubiensis. Not until the middle of the 19th century was a complete translation of the Arabic text published. This was a translation into French by Pierre Amédée Jaubert. More recently sections of the text have been translated for particular regions. In the 1970s a critical edition of the complete Arabic text was published.

Andalusian-American contact

Al-Idrisi's geographical text, Nuzhatul Mushtaq, is often cited by proponents of pre-Columbian Andalusian-Americas contact theories. In this text, al-Idrisi wrote the following on the Atlantic Ocean:

The Commander of the Muslims Ali ibn Yusuf ibn Tashfin sent his admiral Ahmad ibn Umar, better known under the name of Raqsh al-Auzz to attack a certain island in the Atlantic, but he died before doing that. [...] Beyond this ocean of fogs it is not known what exists there. Nobody has the sure knowledge of it, because it is very difficult to traverse it. Its atmosphere is foggy, its waves are very strong, its dangers are perilous, its beasts are terrible, and its winds are full of tempests. There are many islands, some of which are inhabited, others are submerged. No navigator traverses them but bypasses them remaining near their coast. [...] And it was from the town of Lisbon that the adventurers set out known under the name of Mugharrarin [seduced ones], penetrated the ocean of fogs and wanted to know what it contained and where it ended. [...] After sailing for twelve more days they perceived an island that seemed to be inhabited, and there were cultivated fields. They sailed that way to see what it contained. But soon barques encircled them and made them prisoners, and transported them to a miserable hamlet situated on the coast. There they landed. The navigators saw there people with red skin; there was not much hair on their body, the hair of their head was straight, and they were of high stature. Their women were of an extraordinary beauty.

This translation by Professor Muhammad Hamidullah is however questionable, since it reports, after having reached an area of "sticky and stinking waters", the Mugharrarin (also translated as "the adventurers") moved back and first reached an uninhabited island where they found "a huge quantity of sheep the meat of which was bitter and uneatable" and, then, "continued southward" and reached the above reported island where they were soon surrounded by barques and brought to "a village whose inhabitants were often fair-haired with long and flaxen hair and the women of a rare beauty". Among the villagers, one spoke Arabic and asked them where they came from. Then the king of the village ordered them to bring them back to the continent where they were surprised to be welcomed by Berbers.[12][verification needed]

Apart from the marvellous and fanciful reports of this history, the most probable interpretation[citation needed] is that the Mugharrarin reached the Sargasso Sea, a part of the ocean covered by seaweed) which is very close to Bermuda yet one thousand miles away from the American mainland. Then while coming back, they may have landed either on the Azores, or on Madeira or even on the westernmost Canary Island, Hiero (because of the sheep). Last, the story with the inhabited island might have occurred either on Tenerife or on Gran Canaria, where the Mugharrarin presumably met some Guanche tribe. This would explain why some of them could speak Arabic (some sporadic contacts had been maintained between the Canary Islands and Morocco) and why they were quickly deported to Morocco where they were welcomed by Berbers. Yet, the story reported by Idrisi is an undisputable account of a certain knowledge of the Atlantic Ocean by the Arabs and by their Andalusian and Moroccan vassals.

In popular culture

- Al Idrisi is the main character in Tariq Ali's book entitled A Sultan in Palermo.

- Al-Idrisi's works had a profound influence on European writers such as: Marino Sanuto the Elder, Antonio Malfante, Jaume Ferrer and Alonso Fernández de Lugo.

- From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_al-Idrisi